Smyrnaean Paralipomena

While I and Achilleas Chatziconstantinou were doing research for our book «The Smyrna Quay», I indexed hundreds of pages of «Amalthea», the historical newspaper of Smyrna. Thus I amassed various interesting data about the waterfront, the famous «Quai», but at the same time, through news, articles, advertisements, etc., I collected a lot of odd facts about life in the city at that time. Some of them are presented below, followed by other posts that were originally uploaded on Facebook.

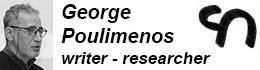

«COVERT DISEASES»

So-called «covert diseases» seem to have plagued the Smyrnaeans in early 1874. The «Raquin pills» promised a remedy.

RAQUIN CAPSULES - with COPAHU balm [Copaiba oil]

COVERT DISEASES

THE RAQUIN CONDOMS [sic]

APPROVED BY THE MEDICAL ACADEMY OF PARIS, which identified in them a formula superior to all others containing COPAHU, and since it was experimentally tested on 100 patients and all 100 of them were healed. The Wise Congregation also acknowledged that RAQUIN PILLS are easy to digest and do not cause any discomfort to the Stomach, or eructation.

I can't imagine how the typesetter of the ad could mix up the words and use the Greek word «KAPOTIA» [condoms] instead of «KATAPOTIA» [pills]. Perhaps he believed prevention was preferable to treatment…

For French speakers, here is more information about the «Raquin pills»:

RAQUIN CAPSULES - with COPAHU balm [Copaiba oil]

COVERT DISEASES

THE RAQUIN CONDOMS [sic]

APPROVED BY THE MEDICAL ACADEMY OF PARIS, which identified in them a formula superior to all others containing COPAHU, and since it was experimentally tested on 100 patients and all 100 of them were healed. The Wise Congregation also acknowledged that RAQUIN PILLS are easy to digest and do not cause any discomfort to the Stomach, or eructation.

I can't imagine how the typesetter of the ad could mix up the words and use the Greek word «KAPOTIA» [condoms] instead of «KATAPOTIA» [pills]. Perhaps he believed prevention was preferable to treatment…

For French speakers, here is more information about the «Raquin pills»:

TRAFFIC ACCIDENTS

In 2015 there were some 13,000 injuries from traffic accidents in Greece, of which almost 1,000 were serious and around 800 fatal. In Smyrna, however, at the beginning of 1874, traffic accidents were just beginning to appear. That was due to the «tramway» –the horse-drawn tram–, which began its operation just at that time, and to the use of the same rail line by the freight train – both terminating at the seaside train station. As pedestrians were not yet accustomed to fixed-track vehicles, they were often careless, resulting in accidents such as the following:

«The eldest of our community's doctors, Mr. M. Masganas, was the victim of a grand accident. On Thursday afternoon, while walking on the waterfront, the company's railway train overturned him and smashed his left foot. The doctors hurried to provide all the aids of science to their fellow patient, but in the end they had to amputate his leg. We hope that Mr. Masganas, who also suffered a head injury, will eventually recover.»

Yet these hopes were dashed. The next day «Amalthea» reported:

«Unfortunately, the misfortune that the old doctor M. Masganas suffered at the railway line of the waterfront proved to be fatal. Despite the efforts of most doctors of the city, he passed away three days after his leg was amputated…»

Another accident occurred a few months later, the victim being a «gardener's apprentice». For obvious reasons, the newspaper devoted only a few words about it:

«Yesterday, the train on the Smyrna waterfront crushed a young man belonging to our community, a gardener's apprentice by profession. The unfortunate man was taken to the hospital in a miserable condition.»

In the editions of the following days, «Amalthea» did not inform us whether the young man survived.

Gradually the people got used to the trains on the waterfront, and so the next accident happened almost three years later, in 1877. This time it was the tramway that was responsible:

«Yesterday, while a seventeen-year-old youngster was strolling carelessly not far from Punta, the tramway cut off both the unfortunate's legs. There is absolutely no hope for his life.»

The use of the railway as a means to end one's life was discovered by a desperate man two years later, in 1879:

«On Wednesday morning, a mentally ill stranger, willing to commit suicide, spread himself on the rails of the waterfront railway. The engineer managed to activate the breaks of the locomotive, and so the unfortunate stranger was not killed, although he was seriously injured.»

Accidents continued to occur several years later, as evidenced by the following news from 1888:

«A distressing accident happened last night on the waterfront. While a young man was walking on the tramway rails, his shoe was caught in the gap between the rails and the pavement, and at that very moment, one of the tramway cars was approaching speedily. The poor young man started to scream to indicate the danger he was in, but unfortunately the driver of the carriage did not decelerate at all, and so the wheels passed over the body of the young man as he was held prisoner there, severely wounding his thigh and leg. Plenty of blood flowed from the wounds, and he was transferred in bad condition to his home. The doctors invited there did not entertain high hopes for the rescue of his life.»

Finally, one more incindent which happened a few days later, narrated in a lyrical mood:

«Only a fortnight after a young fellow citizen, who provided for a large family, was woefully trampled by the waterfront tramway, and already the day before yesterday its iron rails were stained again with the blood of another victim, due to the clumsy way the tramway is operated. A youngster of 17-18 years, working in one of the cafes on the waterfront, tried to get off the horse-drawn tram while it was in motion, but he slipped and fell under the wheels, being fatally wounded in the head.»

All the above took place even before the first automobile appearance in Smyrna…

«The eldest of our community's doctors, Mr. M. Masganas, was the victim of a grand accident. On Thursday afternoon, while walking on the waterfront, the company's railway train overturned him and smashed his left foot. The doctors hurried to provide all the aids of science to their fellow patient, but in the end they had to amputate his leg. We hope that Mr. Masganas, who also suffered a head injury, will eventually recover.»

Yet these hopes were dashed. The next day «Amalthea» reported:

«Unfortunately, the misfortune that the old doctor M. Masganas suffered at the railway line of the waterfront proved to be fatal. Despite the efforts of most doctors of the city, he passed away three days after his leg was amputated…»

Another accident occurred a few months later, the victim being a «gardener's apprentice». For obvious reasons, the newspaper devoted only a few words about it:

«Yesterday, the train on the Smyrna waterfront crushed a young man belonging to our community, a gardener's apprentice by profession. The unfortunate man was taken to the hospital in a miserable condition.»

In the editions of the following days, «Amalthea» did not inform us whether the young man survived.

Gradually the people got used to the trains on the waterfront, and so the next accident happened almost three years later, in 1877. This time it was the tramway that was responsible:

«Yesterday, while a seventeen-year-old youngster was strolling carelessly not far from Punta, the tramway cut off both the unfortunate's legs. There is absolutely no hope for his life.»

The use of the railway as a means to end one's life was discovered by a desperate man two years later, in 1879:

«On Wednesday morning, a mentally ill stranger, willing to commit suicide, spread himself on the rails of the waterfront railway. The engineer managed to activate the breaks of the locomotive, and so the unfortunate stranger was not killed, although he was seriously injured.»

Accidents continued to occur several years later, as evidenced by the following news from 1888:

«A distressing accident happened last night on the waterfront. While a young man was walking on the tramway rails, his shoe was caught in the gap between the rails and the pavement, and at that very moment, one of the tramway cars was approaching speedily. The poor young man started to scream to indicate the danger he was in, but unfortunately the driver of the carriage did not decelerate at all, and so the wheels passed over the body of the young man as he was held prisoner there, severely wounding his thigh and leg. Plenty of blood flowed from the wounds, and he was transferred in bad condition to his home. The doctors invited there did not entertain high hopes for the rescue of his life.»

Finally, one more incindent which happened a few days later, narrated in a lyrical mood:

«Only a fortnight after a young fellow citizen, who provided for a large family, was woefully trampled by the waterfront tramway, and already the day before yesterday its iron rails were stained again with the blood of another victim, due to the clumsy way the tramway is operated. A youngster of 17-18 years, working in one of the cafes on the waterfront, tried to get off the horse-drawn tram while it was in motion, but he slipped and fell under the wheels, being fatally wounded in the head.»

All the above took place even before the first automobile appearance in Smyrna…

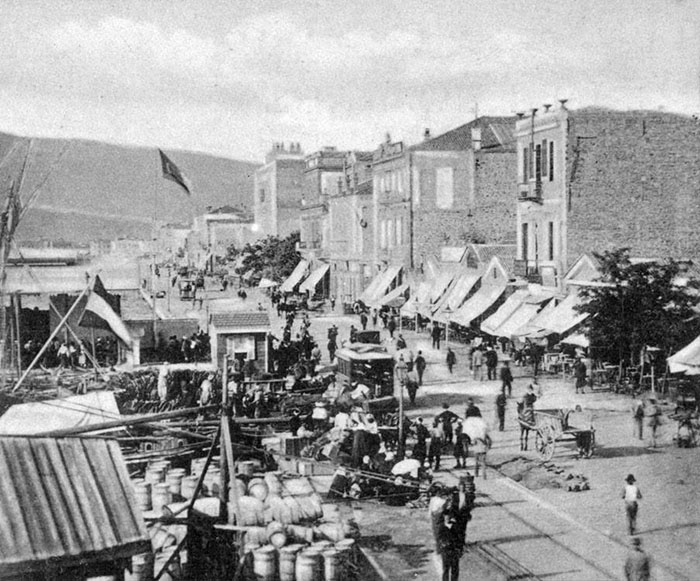

THE AUTHORITIES TAKE MEASURES

The reforms of the Ottoman State and the equality of its citizens regardless of race and religion, promised by the Imperial Decrees of 1839 (Hatt-ı Şerif) and 1856 (Hatt-ı Hümâyun), as well as the Constitution of 1876, did not only contribute to the relative prosperity of the minorities during this period, but they seem to have simultaneously disrupted the habits and customs of the Muslim majority. Thus, in the summer of 1874, the Vali [governor] of Smyrna was forced to take measures:

«The general administration of Smyrna had to abolish the pernicious habit that has recently prevailed in [Turkish] weddings, banquets, etc., i.e. Jewish dancing girls. He announced that those who violate this order will be subject to punishment, including imprisonment and a fine.»

However, just the Jewish dancing girls were threatened with punishment, but not the Turks who took part in the banquett.

Something unprecedented happened two years later, in 1876, in Thyra [Tire], a town near Smyrna, starring Turkish women workers:

«A demonstration took place in Thyra this week in protest against a measure of the authorities which forbids Turkish women to work in non-Muslim properties. The Turkish women were shouting that the measure was unjust, and since otherwise they could not find a way to make a living, they woud be impelled to become beggars. Finally, older women were allowed to work wherever they could.»

It seems that in Thyra a majority of small industries and/or estates were then in the hands of Christians; the fact that the energetic protest of the women was finally crowned with success is also impressive.

In the following year [1877] in the capital, Turkish men on the one hand were neglecting their religious duties, and Turkish women on the other were beginnhng to follow the demands of fashion, wearing translucent «yashmaks» [veils], as well as ultra-modern «feredjes» [full-body cloaks]. Thus, the police were forced to issue strict instructions:

«The police ministry in Constantinople took various measures concerning Turkish men and women. For the men, being true Muslims, it is recommended to go to the mosques regularly as soon the muezzin calls for prayer, and for the women a) to cover their faces with a thick yashmak b) not stand for too long in front of bazaar workshops, and c) not to wear modern feredjes, as well as leggings and shoes of the time of Louis XIV, but to return instead to the ancient traditional clothing.»

Of course, the police instructions had no effect whatsoever, at least on women. A few years later, in the upper social classes, the traditional feredjes had been replaced by the not so conservative «charshaf» [a headscarf that also covered the shoulders].

«The general administration of Smyrna had to abolish the pernicious habit that has recently prevailed in [Turkish] weddings, banquets, etc., i.e. Jewish dancing girls. He announced that those who violate this order will be subject to punishment, including imprisonment and a fine.»

However, just the Jewish dancing girls were threatened with punishment, but not the Turks who took part in the banquett.

Something unprecedented happened two years later, in 1876, in Thyra [Tire], a town near Smyrna, starring Turkish women workers:

«A demonstration took place in Thyra this week in protest against a measure of the authorities which forbids Turkish women to work in non-Muslim properties. The Turkish women were shouting that the measure was unjust, and since otherwise they could not find a way to make a living, they woud be impelled to become beggars. Finally, older women were allowed to work wherever they could.»

It seems that in Thyra a majority of small industries and/or estates were then in the hands of Christians; the fact that the energetic protest of the women was finally crowned with success is also impressive.

In the following year [1877] in the capital, Turkish men on the one hand were neglecting their religious duties, and Turkish women on the other were beginnhng to follow the demands of fashion, wearing translucent «yashmaks» [veils], as well as ultra-modern «feredjes» [full-body cloaks]. Thus, the police were forced to issue strict instructions:

«The police ministry in Constantinople took various measures concerning Turkish men and women. For the men, being true Muslims, it is recommended to go to the mosques regularly as soon the muezzin calls for prayer, and for the women a) to cover their faces with a thick yashmak b) not stand for too long in front of bazaar workshops, and c) not to wear modern feredjes, as well as leggings and shoes of the time of Louis XIV, but to return instead to the ancient traditional clothing.»

Of course, the police instructions had no effect whatsoever, at least on women. A few years later, in the upper social classes, the traditional feredjes had been replaced by the not so conservative «charshaf» [a headscarf that also covered the shoulders].

ROBBERS AND SWINDLERS

In Smyrna of the late 19th century, the greatest threat to public safety were the Christian and Muslim bandit gangs raiding the surrounding countryside. Nonetheless, crime cases, mainly robberies and thefts, also abounded within the city. In fact, some thieves were «imported» from elsewhere, according to the Smyrnaean newspaper «Amalthea» of 3.8.1874.

«The next scene happened at the pier of the passport office.

An Orthodox monk, arriving from abroad, waited for the customs officers to check his luggage, as usual. As he was standing there, a person came and asked if the wallet lying at his feet belonged to him.

While the padre was stooping to get the wallet, a properly dressed young man appeared and rushed against the two, the monk and the one who had showed him the wallet. He immediately started to search the monk. Before the monk could recover from the surprise, the young man began to search the other one too, and before long he found a second wallet on him. The young man claimed that they had stolen it from him and started beating the other one. The victim immediately fled, and the young man rushed after him ostensibly to catch him. In the blink of an eye, they both disappeared.

These two were accomplished purse snatchers. They resorted to this comedy to steal the monk, who later realized that they had taken seven pounds from him – his entire property. Needless to say, these honest persons come to us from Alexandria.»

But even the local thieves did not have any lack of ideas, as reported in a news item of November 1875.

«A civilian was about to pass through the street of our hospital, but he was hesitating. Then, a passer-by took him by the hand hand and led him to Roses Street with great care. But when they separated, the unfortunate man saw that his watch and money were missing.»

Another trick used by swindlers to deceive the naive was the «grupo». Below are two incidents from 1876 and 1880.

«On Monday morning, near the dark tavern, two thieves removed the wallet of a member of our community. The thieves had thrown the grupo (a pouch containing coins of small value) on the street, and the unfortunate man, who thought he had found a treasure, attempted to get it. At the same time, however, another person showed up asking for a share and while they were about to distribute the find, his wallet was seized!»

«The day before yesterday, a member of our community, a stranger (from Phocaea), was swindled by some thieves using the grupo. They persuaded him to follow them to the Gout mill in order to split the find fraternally, but there they attacked him and snatched all his money. The grupo is a small, securely fastened pouch, containing fiver coins. When the thief gets a whiff of a naive stranger, he deliberately throws the pouch to the ground, while his partner,supposedly passing by, finds it in front of the stranger's eyes. He then offers to split the find, since luck has favored them both. If the stranger accepts the proposal, as it always happens, he is led to a remote place, where the criminals attack him and strip him bare.»

One is never safe, not even from his friends, as «Amalthea» informs us in the summer of 1879.

«Yesterday evening a young man encountered a friend of his, a money collector working for a bank. He snatched his bag containing 270 liras, supposedly as a joke, and then asked for a treat in order to return it. His friend complied, but as they were going to a tavern, the young man holding the money disappeared. This is apparently a new kind of theft.»

Most of the time, however, thieves simply robbed their victims using, or threatening to use, violence, as a grocer was robbed in 1875.

«Yesterday evening, in a Frank Street full of people, thieves snatched the small chest where a grocer was holding his money. Apparently the thieves are currently triumphing, because their achievements are many.»

Not all thieves were greedy though. Some even showed a little compassion for their victims.

«On Sunday morning [30.3.1877] a notorious thief, whose deeds defy description, captured a passer-by and, after emptying his pockets, he said: “It is already the fourth time that you have fallen into my hands. That is enough. From now on you can move around undisturbed, because I will not touch you again.”»

1880 was not a good year for thieves. Their earnings seemed to have dropped significantly, and in addition they were running serious business risks.

«Yesterday morning, on the waterfront, a thief snatched the wallet of a poor passer-by, containing only forty piasters. Fortunately, the criminal was immediately arrested by some civilians and thoroughly beaten up.»

Risking possible impoverishment, at the end of that year (1880) the criminals had to innovate in order to increase their income.

«Criminals posted a statement on a wall in Tabakhane, announcing that if any passer-by who falls into their hands has less than 3 medjits [silver coins] on him, or if he does not have a watch, he will be beaten or stabbed!»

The announcement does not specify whether the severity of their victims' punishment would be inversely proportional to the booty. Would those who carried something valuable just be beaten, while the moneyless ones would suffer knife stabs?

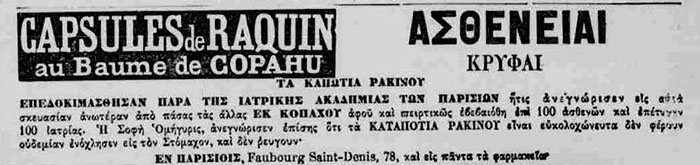

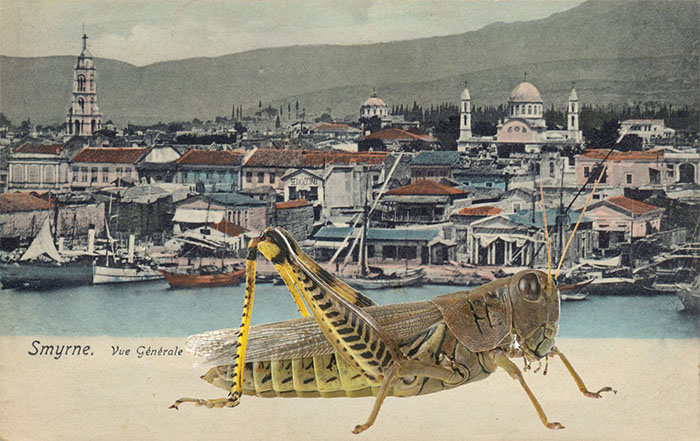

(The photo shows the port of Smyrna around the Passport office, visible at the center left)

«The next scene happened at the pier of the passport office.

An Orthodox monk, arriving from abroad, waited for the customs officers to check his luggage, as usual. As he was standing there, a person came and asked if the wallet lying at his feet belonged to him.

While the padre was stooping to get the wallet, a properly dressed young man appeared and rushed against the two, the monk and the one who had showed him the wallet. He immediately started to search the monk. Before the monk could recover from the surprise, the young man began to search the other one too, and before long he found a second wallet on him. The young man claimed that they had stolen it from him and started beating the other one. The victim immediately fled, and the young man rushed after him ostensibly to catch him. In the blink of an eye, they both disappeared.

These two were accomplished purse snatchers. They resorted to this comedy to steal the monk, who later realized that they had taken seven pounds from him – his entire property. Needless to say, these honest persons come to us from Alexandria.»

But even the local thieves did not have any lack of ideas, as reported in a news item of November 1875.

«A civilian was about to pass through the street of our hospital, but he was hesitating. Then, a passer-by took him by the hand hand and led him to Roses Street with great care. But when they separated, the unfortunate man saw that his watch and money were missing.»

Another trick used by swindlers to deceive the naive was the «grupo». Below are two incidents from 1876 and 1880.

«On Monday morning, near the dark tavern, two thieves removed the wallet of a member of our community. The thieves had thrown the grupo (a pouch containing coins of small value) on the street, and the unfortunate man, who thought he had found a treasure, attempted to get it. At the same time, however, another person showed up asking for a share and while they were about to distribute the find, his wallet was seized!»

«The day before yesterday, a member of our community, a stranger (from Phocaea), was swindled by some thieves using the grupo. They persuaded him to follow them to the Gout mill in order to split the find fraternally, but there they attacked him and snatched all his money. The grupo is a small, securely fastened pouch, containing fiver coins. When the thief gets a whiff of a naive stranger, he deliberately throws the pouch to the ground, while his partner,supposedly passing by, finds it in front of the stranger's eyes. He then offers to split the find, since luck has favored them both. If the stranger accepts the proposal, as it always happens, he is led to a remote place, where the criminals attack him and strip him bare.»

One is never safe, not even from his friends, as «Amalthea» informs us in the summer of 1879.

«Yesterday evening a young man encountered a friend of his, a money collector working for a bank. He snatched his bag containing 270 liras, supposedly as a joke, and then asked for a treat in order to return it. His friend complied, but as they were going to a tavern, the young man holding the money disappeared. This is apparently a new kind of theft.»

Most of the time, however, thieves simply robbed their victims using, or threatening to use, violence, as a grocer was robbed in 1875.

«Yesterday evening, in a Frank Street full of people, thieves snatched the small chest where a grocer was holding his money. Apparently the thieves are currently triumphing, because their achievements are many.»

Not all thieves were greedy though. Some even showed a little compassion for their victims.

«On Sunday morning [30.3.1877] a notorious thief, whose deeds defy description, captured a passer-by and, after emptying his pockets, he said: “It is already the fourth time that you have fallen into my hands. That is enough. From now on you can move around undisturbed, because I will not touch you again.”»

1880 was not a good year for thieves. Their earnings seemed to have dropped significantly, and in addition they were running serious business risks.

«Yesterday morning, on the waterfront, a thief snatched the wallet of a poor passer-by, containing only forty piasters. Fortunately, the criminal was immediately arrested by some civilians and thoroughly beaten up.»

Risking possible impoverishment, at the end of that year (1880) the criminals had to innovate in order to increase their income.

«Criminals posted a statement on a wall in Tabakhane, announcing that if any passer-by who falls into their hands has less than 3 medjits [silver coins] on him, or if he does not have a watch, he will be beaten or stabbed!»

The announcement does not specify whether the severity of their victims' punishment would be inversely proportional to the booty. Would those who carried something valuable just be beaten, while the moneyless ones would suffer knife stabs?

(The photo shows the port of Smyrna around the Passport office, visible at the center left)

CHRISTIAN SUFFERINGS

Although in the last quarter of the 19th century the Ottoman State tried to advocate certain reforms in order to be transformed into a modern European state one day, old habits were not easy to eradicate. One of them was slavery, which had theoretically been abolished. In practice, however, some people still kept slaves, and also procured new ones, as we learn from «Amalthea» in February 1876.

«Four slaves, two boys and two girls, bought by an Ottoman nobleman of Magnesia [Manisa, a city 80 km from Smyrna], arrived in Smyrna last week. When he learned of this, the honorable Hayri Bey, director of the passport office, ordered the slaves to be seized and taken to the governor's building.»

The newspaper does not inform us about the further fate of the unfortunate young people, nor whether the Ottoman nobleman suffered the consequences of violating the law, which is very doubtful. One month later, another news item describes the abuse of a Smyrna merchant of French descent in Uşak:

«It is reported to ‘La Réforme’ [a French-language newspaper of Smyrna] from Uşak [a city in the interior of Smyrna prefecture] that twenty or so young Turkish scoundrels, some of them twenty-five-year-olds, insulted Mr. A. Giraud, a French merchant, by screaming ‘Giaour [infidel]! Giaour! Frank!’ Mr. Giraud went to the kaymakam [prefect] and demanded that these young scoundrels be arrested within 24 hours, otherwise he would telegraph to his consul in Smyrna. When the kaymakam learned of this, he hastened to order the arrest and imprisonment of the guilty ones. The following notice was posted in the markets and the mosques the next day:

‘It is strictly forbidden that the faithful stone Christians and call them Frank giaours. Those who do not comply with this provision will be fined 10 to 20 medjids [silver coins] and sentenced to 6 to 12 months in prison.’»

The immediate reaction of the authorities is impressive, probably because Mr. Giraud was a Western national. The same was not true for the Orthodox, as «Amalthea» informs us in the summer of the same year.

«… it is reported from Söke [a town near Ephesus] that three Turkish peasants (Peloponnesians) captured a Christian who was digging for liquorice roots in his field and put him under the oxen yoke used to plow his fields. And because this unfortunate could not serve as an animal, the criminals beat him so much that they left him half dead. After a few days the kaymakam, on learning what had happened, ordered the arrest of the Turks. Since they denied everything, the just commander suggested that the wounded Christian should present Turks as witnesses, but since such witnesses did not of course exist, the criminals were released, after first stating under oath that the Christian was lying! We hope that this lawless state will stop, and the criminals will be severely punished.»

The Turkish farmers described as Peloponnesians must have been refugees or refugee descendants from Peloponnese, and therefore probably they did not particularly like Christians. However, the impunity that prevailed in the countryside apparently did not exist to the same extent in Smyrna and its suburbs, as we learn from another news item from the beginning of 1877.

«There exist serious complaints against the agha of Cordelio [a suburb of Smyrna] who, apparently recollecting ancient times, is trying to illegaly enrich himself. One of these days he brutally beat two Christian villagers from Çiğli, to release them only after receiving 70 piasters. When the matter was reported to Yasin Bey, the honorable commander of the gendarmerie, he summoned the above agha and is already interrogating him. We believe that he will punish him.»

«Four slaves, two boys and two girls, bought by an Ottoman nobleman of Magnesia [Manisa, a city 80 km from Smyrna], arrived in Smyrna last week. When he learned of this, the honorable Hayri Bey, director of the passport office, ordered the slaves to be seized and taken to the governor's building.»

The newspaper does not inform us about the further fate of the unfortunate young people, nor whether the Ottoman nobleman suffered the consequences of violating the law, which is very doubtful. One month later, another news item describes the abuse of a Smyrna merchant of French descent in Uşak:

«It is reported to ‘La Réforme’ [a French-language newspaper of Smyrna] from Uşak [a city in the interior of Smyrna prefecture] that twenty or so young Turkish scoundrels, some of them twenty-five-year-olds, insulted Mr. A. Giraud, a French merchant, by screaming ‘Giaour [infidel]! Giaour! Frank!’ Mr. Giraud went to the kaymakam [prefect] and demanded that these young scoundrels be arrested within 24 hours, otherwise he would telegraph to his consul in Smyrna. When the kaymakam learned of this, he hastened to order the arrest and imprisonment of the guilty ones. The following notice was posted in the markets and the mosques the next day:

‘It is strictly forbidden that the faithful stone Christians and call them Frank giaours. Those who do not comply with this provision will be fined 10 to 20 medjids [silver coins] and sentenced to 6 to 12 months in prison.’»

The immediate reaction of the authorities is impressive, probably because Mr. Giraud was a Western national. The same was not true for the Orthodox, as «Amalthea» informs us in the summer of the same year.

«… it is reported from Söke [a town near Ephesus] that three Turkish peasants (Peloponnesians) captured a Christian who was digging for liquorice roots in his field and put him under the oxen yoke used to plow his fields. And because this unfortunate could not serve as an animal, the criminals beat him so much that they left him half dead. After a few days the kaymakam, on learning what had happened, ordered the arrest of the Turks. Since they denied everything, the just commander suggested that the wounded Christian should present Turks as witnesses, but since such witnesses did not of course exist, the criminals were released, after first stating under oath that the Christian was lying! We hope that this lawless state will stop, and the criminals will be severely punished.»

The Turkish farmers described as Peloponnesians must have been refugees or refugee descendants from Peloponnese, and therefore probably they did not particularly like Christians. However, the impunity that prevailed in the countryside apparently did not exist to the same extent in Smyrna and its suburbs, as we learn from another news item from the beginning of 1877.

«There exist serious complaints against the agha of Cordelio [a suburb of Smyrna] who, apparently recollecting ancient times, is trying to illegaly enrich himself. One of these days he brutally beat two Christian villagers from Çiğli, to release them only after receiving 70 piasters. When the matter was reported to Yasin Bey, the honorable commander of the gendarmerie, he summoned the above agha and is already interrogating him. We believe that he will punish him.»

THE EIGHTH PLAGUE OF EGYPT

« … I will bring locusts into your country tomorrow … They will devour … every tree that is growing in your fields …» - Apparently, the situation did not improve much since the time of Moses, as we learn from «Amalthea» in May 1876, which mocks the efforts of magicians and hodjas to fight the locust plague in the interior of Smyrna prefecture:

«The blessings and the exorcisms of the magician from Denizli [a city 180 km SE of Smyrna] and the 70 hodjas who went to Keles Ovası to exterminate the locusts had absolutely no effect. The vicious bug, whose wings have already sprouted, causes great damage to the farmers, who had to feed those wise men and benefactors of the community from their meagre surplus and to pay large amounts for the travel expenses of their return. The kaymakam of Ödemiş [a town 75 km SE of Izmir] is indeed commendable for having allowed such a quackery, while his superiors vehemently ordered him to chase the locusts.»

The following month, locusts flooded the city of Smyrna, as well as the sea.

«So many locusts fell these days into the sea, that the stench emitted by them in many places is unbearable. On Saturday afternoon the town hall ordered to transport by carriages the locusts that had descended at Dolma to the Jewish cemetery, where they dug pits and buried them. Nevertheless, similar provisions are needed elsewhere too.»

The newspaper fails to inform us whether locusts of different religious beliefs were buried in the respective Muslim and Christian cemeteries of the city. However, apart from Smyrna, Kato Panagia (now Çiftlik, a village in the Erythraean peninsula 80 km W of Smyrna) was to be hit a little later by the omnivorous bug, in fact following strong southerly winds and the «vine-destroying worm» (Phylloxera), which caused great damage to the vineyards.

«… Finally it was destined that the capstone of these accidents would strike. It was destined, I repeat, that the remnants left by the vine-destroying worm be completely devoured by the corrupting locusts, which visited this unfortunate place 15 days ago. They fell furiously in swarms against everything and devoured the cotton plantations, the aniseed, the onions and the melon gardens to the roots. Unsaturated, they also fell against the vines, the last and only hope of the inhabitants, whose main product is raisins. Having lost their ultimate hope, they came to absolute despair.»

Apart from crops, however, locusts also created problems for … rail transport.

«The swarms of locusts are becoming larger day by day, and in certain places the trains of both railway lines can barely move. That's because the iron rails are full of bugs, which when killed are transformed into a slimy material that hinders the wheels. The stench is great in some places. Unfortunately, as we also said in the past, appropriate measures were not taken in time to eradicate the plague. However, in Budja [a suburb of Smyrna] the persecution has already begun, thanks mainly to Smyrnaeans residing there. They began to gather the destructive bug, paying 20 piasters for each oka [1,2 kg] delivered …»

Thirty years later, in December 1913, the methods for controlling the locust plague had evolved, focusing on prevention.

«It is officially announced by the Prefecture that the deadline for the delivery of ten okas of locust eggs, which has expired at the 15th of this month, has been extended until next January 1. By decision of the Special Council, both government and military officials, as well as gendarmerie officers, must also deliver the corresponding quantity of ten okas of eggs.»

Everyone, without exception, was obliged to collect and deliver 10 okas (12 kg) of locust eggs, even Greek nationals, and in fact by special agreement.

«According to the treaty conducted after the war, it was formally decided that Greek citizens in Turkey would have to pay the road tax and deliver the corresponding for each citizen quantity of ten okas of locust eggs.»

Of course, as is often the case in similar occasions, some crooks exploited the opportunity to take advantage of the situation.

«About the locusts - The signer declares that everyone who wants to be supplied with locust eggs at the price of 15 octarakia [2-piaster coins] for 10 okas should apply to the Hamidiye dock in Smyrna, or to my shop next to the management office of the egg depot. I will be obliged to give to the buyer the relevant receipt – Hadji-Papelis.»

With 15 octarakia (30/100 of a lira), those interested could buy the required 10 okas of locust eggs and deliver them to the relevant agency. The fact that the seller's shop was located next to the state depot where the eggs were collected does not seem to have raised suspicions of dubious transactions between him and the depot guards.

Shortly before the deadline, the «Smyrna Echo» column of «Amalthea» warned those who had not yet carried out their duty:

«… Do not forget that you have to obtain twelve or fifteen okas of locusts, or send 15 2-piaster coins to the responsible agency. It is not enough that the awful bug fell upon the fields and caused the villagers extra chores to exterminate it, it also fell upon the wallets of the citizens, the inhabitants of the cities, to relieve them of 15 coins, as a kind of gratuity to it for the upcoming holidays. It is therefore necessary for those who have neglected it to comply with the government order, because after December 31, everyone who has not payed the 15 2-piaster coins will be fined one lira or imprisoned for a few days.»

«The blessings and the exorcisms of the magician from Denizli [a city 180 km SE of Smyrna] and the 70 hodjas who went to Keles Ovası to exterminate the locusts had absolutely no effect. The vicious bug, whose wings have already sprouted, causes great damage to the farmers, who had to feed those wise men and benefactors of the community from their meagre surplus and to pay large amounts for the travel expenses of their return. The kaymakam of Ödemiş [a town 75 km SE of Izmir] is indeed commendable for having allowed such a quackery, while his superiors vehemently ordered him to chase the locusts.»

The following month, locusts flooded the city of Smyrna, as well as the sea.

«So many locusts fell these days into the sea, that the stench emitted by them in many places is unbearable. On Saturday afternoon the town hall ordered to transport by carriages the locusts that had descended at Dolma to the Jewish cemetery, where they dug pits and buried them. Nevertheless, similar provisions are needed elsewhere too.»

The newspaper fails to inform us whether locusts of different religious beliefs were buried in the respective Muslim and Christian cemeteries of the city. However, apart from Smyrna, Kato Panagia (now Çiftlik, a village in the Erythraean peninsula 80 km W of Smyrna) was to be hit a little later by the omnivorous bug, in fact following strong southerly winds and the «vine-destroying worm» (Phylloxera), which caused great damage to the vineyards.

«… Finally it was destined that the capstone of these accidents would strike. It was destined, I repeat, that the remnants left by the vine-destroying worm be completely devoured by the corrupting locusts, which visited this unfortunate place 15 days ago. They fell furiously in swarms against everything and devoured the cotton plantations, the aniseed, the onions and the melon gardens to the roots. Unsaturated, they also fell against the vines, the last and only hope of the inhabitants, whose main product is raisins. Having lost their ultimate hope, they came to absolute despair.»

Apart from crops, however, locusts also created problems for … rail transport.

«The swarms of locusts are becoming larger day by day, and in certain places the trains of both railway lines can barely move. That's because the iron rails are full of bugs, which when killed are transformed into a slimy material that hinders the wheels. The stench is great in some places. Unfortunately, as we also said in the past, appropriate measures were not taken in time to eradicate the plague. However, in Budja [a suburb of Smyrna] the persecution has already begun, thanks mainly to Smyrnaeans residing there. They began to gather the destructive bug, paying 20 piasters for each oka [1,2 kg] delivered …»

Thirty years later, in December 1913, the methods for controlling the locust plague had evolved, focusing on prevention.

«It is officially announced by the Prefecture that the deadline for the delivery of ten okas of locust eggs, which has expired at the 15th of this month, has been extended until next January 1. By decision of the Special Council, both government and military officials, as well as gendarmerie officers, must also deliver the corresponding quantity of ten okas of eggs.»

Everyone, without exception, was obliged to collect and deliver 10 okas (12 kg) of locust eggs, even Greek nationals, and in fact by special agreement.

«According to the treaty conducted after the war, it was formally decided that Greek citizens in Turkey would have to pay the road tax and deliver the corresponding for each citizen quantity of ten okas of locust eggs.»

Of course, as is often the case in similar occasions, some crooks exploited the opportunity to take advantage of the situation.

«About the locusts - The signer declares that everyone who wants to be supplied with locust eggs at the price of 15 octarakia [2-piaster coins] for 10 okas should apply to the Hamidiye dock in Smyrna, or to my shop next to the management office of the egg depot. I will be obliged to give to the buyer the relevant receipt – Hadji-Papelis.»

With 15 octarakia (30/100 of a lira), those interested could buy the required 10 okas of locust eggs and deliver them to the relevant agency. The fact that the seller's shop was located next to the state depot where the eggs were collected does not seem to have raised suspicions of dubious transactions between him and the depot guards.

Shortly before the deadline, the «Smyrna Echo» column of «Amalthea» warned those who had not yet carried out their duty:

«… Do not forget that you have to obtain twelve or fifteen okas of locusts, or send 15 2-piaster coins to the responsible agency. It is not enough that the awful bug fell upon the fields and caused the villagers extra chores to exterminate it, it also fell upon the wallets of the citizens, the inhabitants of the cities, to relieve them of 15 coins, as a kind of gratuity to it for the upcoming holidays. It is therefore necessary for those who have neglected it to comply with the government order, because after December 31, everyone who has not payed the 15 2-piaster coins will be fined one lira or imprisoned for a few days.»

EPIDEMICS IN SMYRNA

Like the rest of the East, Smyrna has often been plagued in relatively recent times by epidemics such as the plague, cholera and smallpox, with victims often numbering in the thousands.

The plague (the «black death») visited the city in the years 1678, 1711, 1741, 1751, 1765, 1778, 1784, 1813, 1818, 1831, 1837 and 1838-39. In 1813, during the deadliest of these epidemics, 45-50,000 of the 100,000 inhabitants died, while in 1837, in a population of 130,000, 5,227 people were affected, of whom 4,831 expired. A few cases occurred also in the summer of 1922. Strict measures were then taken and a general compulsory vaccination was ordered, resulting in a quick suppression of the disease.

Cholera broke out in 1831, 1848, 1854-1855, 1865, 1893, 1910-11 and 1913, mainly affecting people over the age of 50. During the epidemic of 1831, the first in the Ottoman Empire, in a population of 80,000 inhabitants there were 17,000 cases, of which 7,000 were fatal, The disease was preceded by plague during the same year. On the next visit of cholera, in 1848, there were 2,129 deaths in a population of 100,000 inhabitants.

We do not have much information about smallpox before 1841, when it was first recorded. The disease, which despite systematic vaccination was decimating the population, especially young children, returned in 1871, 1888, 1896, 1903, 1909 and 1913, the last time in parallel with the cholera epidemic.

Finally, at the beginning of 1918, in the middle of the war, a typhus epidemic («lice disease») occurred in Smyrna with 20,000 cases, of which 2,000 were fatal.

As soon as an epidemic broke out, the patients were transported to special infirmaries («Mortakia») by the «mortis», i.e. those who had survived the disease and had acquired immunity. Such infirmaries, one or more for each ethnic community, began to be erected at the city limits from 1840 onwards. The dead were disinfected in large pits with lime before being buried in cemeteries.

The rest of the inhabitants of Smyrna were confined in their houses or hurried to leave the city, resorting to the surrounding mountains and suburbs, at the entrance of which they were fumigated or sprinkled with phenol by the locals. Beggars were not excluded from the exodus. During the cholera epidemic of 1855, everyone without exception left, returning to their places of origin, a fact that the Smyrnaean press welcomed with relief. The few inhabitants who still circulated in the streets carried huge walking sticks, so that no one could approach them.

Quarters with a high prevalence of the epidemic were isolated with ropes, and old houses where the sick had died were demolished or set on fire. Schools, cafes and taverns were closed, in contrast to churches, where crowds gathered for prayers and processions. As for food, vegetables were banned and confiscated, especially cucumbers and lettuces, while the remaining food stuffs and various other items, especially coins, were immersed in vinegar for disinfection.

With the advancement of science and the introduction of personal hygiene in the last century, we had almost forgotten that people used to experience such situations. The coronavirus came to remind us of them…

Here is the Turkish translation by Ayşen Tekşen.

Source: Ch. Solomonidis, Medicine in Smyrna.

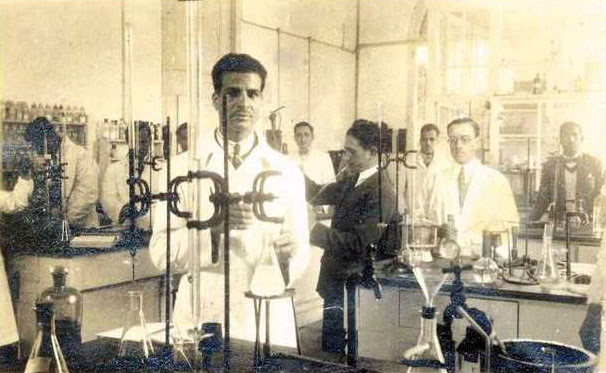

In the photo: A pharmacy in Smyrna.

The plague (the «black death») visited the city in the years 1678, 1711, 1741, 1751, 1765, 1778, 1784, 1813, 1818, 1831, 1837 and 1838-39. In 1813, during the deadliest of these epidemics, 45-50,000 of the 100,000 inhabitants died, while in 1837, in a population of 130,000, 5,227 people were affected, of whom 4,831 expired. A few cases occurred also in the summer of 1922. Strict measures were then taken and a general compulsory vaccination was ordered, resulting in a quick suppression of the disease.

Cholera broke out in 1831, 1848, 1854-1855, 1865, 1893, 1910-11 and 1913, mainly affecting people over the age of 50. During the epidemic of 1831, the first in the Ottoman Empire, in a population of 80,000 inhabitants there were 17,000 cases, of which 7,000 were fatal, The disease was preceded by plague during the same year. On the next visit of cholera, in 1848, there were 2,129 deaths in a population of 100,000 inhabitants.

We do not have much information about smallpox before 1841, when it was first recorded. The disease, which despite systematic vaccination was decimating the population, especially young children, returned in 1871, 1888, 1896, 1903, 1909 and 1913, the last time in parallel with the cholera epidemic.

Finally, at the beginning of 1918, in the middle of the war, a typhus epidemic («lice disease») occurred in Smyrna with 20,000 cases, of which 2,000 were fatal.

As soon as an epidemic broke out, the patients were transported to special infirmaries («Mortakia») by the «mortis», i.e. those who had survived the disease and had acquired immunity. Such infirmaries, one or more for each ethnic community, began to be erected at the city limits from 1840 onwards. The dead were disinfected in large pits with lime before being buried in cemeteries.

The rest of the inhabitants of Smyrna were confined in their houses or hurried to leave the city, resorting to the surrounding mountains and suburbs, at the entrance of which they were fumigated or sprinkled with phenol by the locals. Beggars were not excluded from the exodus. During the cholera epidemic of 1855, everyone without exception left, returning to their places of origin, a fact that the Smyrnaean press welcomed with relief. The few inhabitants who still circulated in the streets carried huge walking sticks, so that no one could approach them.

Quarters with a high prevalence of the epidemic were isolated with ropes, and old houses where the sick had died were demolished or set on fire. Schools, cafes and taverns were closed, in contrast to churches, where crowds gathered for prayers and processions. As for food, vegetables were banned and confiscated, especially cucumbers and lettuces, while the remaining food stuffs and various other items, especially coins, were immersed in vinegar for disinfection.

With the advancement of science and the introduction of personal hygiene in the last century, we had almost forgotten that people used to experience such situations. The coronavirus came to remind us of them…

Here is the Turkish translation by Ayşen Tekşen.

Source: Ch. Solomonidis, Medicine in Smyrna.

In the photo: A pharmacy in Smyrna.

QUARANTINE IN 1919 SMYRNA

Lock-down - but also food delivery! - have also existed in the past. Here is how, in 1919, the Greek authorities of Smyrna treated a case where plague was probably the cause of a death. Many years later, the then seven-year-old Peter Polycarp Galdies, the son of the deceased, recounts:

«As soon as the death report was handed to the authorities for burial permission, a sanitary officer arrived home with personnel and fumigating equipment. They took charge of the burial of the body, while we in the house were all vaccinated; I remember, so scared was I, that I ran to hide behind a large broom in the corner of the kitchen, but with no success, for I was soon found and vaccinated as all the others did.

The whole family was ordered in the saloon [Gr. saloni = dining/living room], which was also the front living room, and were told that we were to sleep in this room too. They closed hermetically and sealed with paper and glue all the window frames and panes, and the same was done to the door leading from the sitting room to the bedroom. The room where my father died was emptied completely of mattresses, pillows, bed covers, curtains etc. Only the naked bed frame, which was metallic, was left. The door leading to the hall, as well as the window facing the entrance, were thoroughly locked and plastered with newspaper, every fissure, and again glued paper all around the door and window frames; as soon as this was done they placed a huge brazier in the middle of the room, a lot of sulfur powder was fumed on the charcoal fire, and immediately closed the door of the sitting room; and again the same sealing procedure was repeated from the outside, thus isolating completely the mortuary room.

The whole house was fumigated and sprayed, and we were ordered not to go out of the house for forty days. Food would be provided by the authorities from the restaurant. A Greek guard was placed outside the door, with strict orders that no one should be allowed in or out of the house. It was arranged that relatives were to look after the animals in the plot adjacent to our house; one was instructed to grass the goat, another would look after the rabbits and chicken.

The first days of confinement were very sad and painful. We did not stop crying for the great loss of our father and for the uncertain future of the family. The sanitary authorities were very generous and good to us, we were authorised to order all the food we wished to have every day without limit of cost and quantity. My elder sisters were using their time mostly reading and studying school books to catch up with their future lessons, whilst I and my young sister were spending our time playing with dolls.»

«As soon as the death report was handed to the authorities for burial permission, a sanitary officer arrived home with personnel and fumigating equipment. They took charge of the burial of the body, while we in the house were all vaccinated; I remember, so scared was I, that I ran to hide behind a large broom in the corner of the kitchen, but with no success, for I was soon found and vaccinated as all the others did.

The whole family was ordered in the saloon [Gr. saloni = dining/living room], which was also the front living room, and were told that we were to sleep in this room too. They closed hermetically and sealed with paper and glue all the window frames and panes, and the same was done to the door leading from the sitting room to the bedroom. The room where my father died was emptied completely of mattresses, pillows, bed covers, curtains etc. Only the naked bed frame, which was metallic, was left. The door leading to the hall, as well as the window facing the entrance, were thoroughly locked and plastered with newspaper, every fissure, and again glued paper all around the door and window frames; as soon as this was done they placed a huge brazier in the middle of the room, a lot of sulfur powder was fumed on the charcoal fire, and immediately closed the door of the sitting room; and again the same sealing procedure was repeated from the outside, thus isolating completely the mortuary room.

The whole house was fumigated and sprayed, and we were ordered not to go out of the house for forty days. Food would be provided by the authorities from the restaurant. A Greek guard was placed outside the door, with strict orders that no one should be allowed in or out of the house. It was arranged that relatives were to look after the animals in the plot adjacent to our house; one was instructed to grass the goat, another would look after the rabbits and chicken.

The first days of confinement were very sad and painful. We did not stop crying for the great loss of our father and for the uncertain future of the family. The sanitary authorities were very generous and good to us, we were authorised to order all the food we wished to have every day without limit of cost and quantity. My elder sisters were using their time mostly reading and studying school books to catch up with their future lessons, whilst I and my young sister were spending our time playing with dolls.»